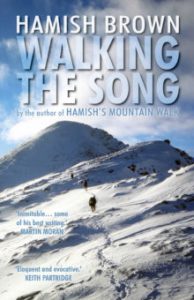

A Day of Glory Given is one chapter in the recently published book by Hamish Brown entitled Walking the Song. As his Wikipedia entry reminds us, Hamish Brown M.B.E. is a professional writer, lecturer and photographer specialising in mountain and outdoor topics. He is best known for his walking exploits in the Scottish Highlands, having completed multiple rounds of the Munros and being the first person to walk all the Munros in a single trip with only ferries and a bicycle as means of transport.

A Day of Glory Given is one chapter in the recently published book by Hamish Brown entitled Walking the Song. As his Wikipedia entry reminds us, Hamish Brown M.B.E. is a professional writer, lecturer and photographer specialising in mountain and outdoor topics. He is best known for his walking exploits in the Scottish Highlands, having completed multiple rounds of the Munros and being the first person to walk all the Munros in a single trip with only ferries and a bicycle as means of transport.

We are grateful to Hamish Brown and his publishers the Sandstone Press for permission to share his day out from Rhenigidale with other friends of Gatliff Trust Youth Hostels.

Only a hill; but all of life to me,

up there, between the sunset and the sea.

Geoffrey Winthrop Young

A step onto the terrace at seven o’clock revealed Venus brightest among the frosted stars and only a cuticle of moon. Beyond the placid sheen of sea the light on Scalpay winked its friendly presence. Everything pointed to respite from a riotous week of dead-of-winter storms. And it was Christmas Day in the Hebrides.

Setting off an hour later from Reinigeadal (Rhenigidal) Todun was just visible, as if the big hill shied from meeting the new day. The summit loomed ghostly white with fresh snow – as if the storms had been stopped in their tracks and forced to precipitate and now had no evil left in them. I drove, cannily, up the steep hairpins, but all was wet below the snowline and the road had been treated. A dozen years ago there had been no road to Reinigeadal and the hamlet was dying. People reached it by sea or by a footpath from Tarbert over a thousand foot pass in the hills and a dizzy drop to sea level again to follow the cliffs round Loch Trolamaraig. The postie had to walk the path regularly.

‘Driving the road to Reinigeadal rather makes you appreciate walking’ was the expressed feelings of a Spanish lad, Enrique, who with a Czech girl, Ivana, had taken the chance of a cosy hostel Christmas away from work in Inverness. Even if it was the worst time of year for a journey they had travelled by bus to Ullapool, crossed in the ferry Isle of Lewis to Stornoway, hired a car and driven south and arrived, not a moment too soon, in the smothering dark of late night at what they felt was the end of the world. The Reinigeadal road starts where the arterial A859 circles An Cliseam, the highest summit – the only Corbett – in the Outer Isles and plunges down to sea level to run along Loch Maraig before rising brutally to the pass by Todun, a crossing with steep inclines and hairpins both fore and aft. Heading out in winter there’s always a feeling of relief on reaching the A859.

The A859 is the main road, the only road, from Stornoway to Tarbert and on to South Harris and ferries to the gentler southern islands. Heading north from our junction the road still swoops and climbs with some exuberance, passes through the biggest wood on the island (nature trails), touches the headwaters of Loch Seaforth and Loch Erisort, and runs through the three mile straggle of Baile Alein (Balalan), where I stopped.

I had drawn in on reaching the A859 hoping Enrique and Ivana would soon follow and I could watch their car’s headlights wander against the jet-black landscape. Instead, I saw day come up over the hills, tentatively tinting and toning the sky in subtleties too difficult to describe but surely drawn from a subdued palette of pearl, citrine, topaz, beryl, jade, coral, amber, saffron, turquoise …

Nearing the woods a hind and her calf of the year stood silhouetted on a rise and, thrice, snipe rose, ricocheting off, from the ditches. A sea eagle came at me along the road, alarmingly like some attacking aircraft, and then casually lifted over the van. When I drew in at Balalan geese went flying off in echoes of their own laughter. The world was awake. Of humans, there was one dog walker being towed along the road.

From An Cliseam the highest hills of Harris line up westwards to end with an island hill on Scarp; another line of bulky rather than beautiful hills are lined left of the road I’d travelled and the most northerly of these is Roineabhal (Roineval). Only a modest 281 metres it has an isolated prominence and catches the eye when seen from afar, a good objective for Christmas at the end of a weary winter.

A cold start I had of it, the puddles on the initial farm track feathering over with ice as I walked and my toes soon pinched with cold in my wee wellies. Turning off all too soon I splashed over the well-named Allt Dubh and faced several kilometres of moor to reach the upthrust of hill. To start I followed a fence line, with one side heathery, the other starved grassland, the russet and the tired tawny. No hay camino, se hace camino al andar – there is no road; the road is made by walking.

My fence line led along to a cropped grassy knoll above the outflow of Loch Stranndabhat, oddly the only loch I would pass near on my pilgrimage. The loch’s south end, two kilometres off, lay by the A859 and often the buzz of a vehicle on the road came like an annoying insect and then vanished again. The loch waters lay unruffled in metallic tints with sharp-cut reflections. Nothing stirred. Three silent sheep wandered up and stood eyeing me speculatively but, receiving nothing, turned and went their way. On setting off a grouse exploded at my feet. Had it kept ‘cooried doon’ I would not have noticed it. Grouse and conversational ravens now and then were the birds of those moorland flanks, an undulating, worn-out landscape, interrupted by the hollows of three running streams I’d have to cross. By the lochside would be too boggy, higher too heathery, so the middle way was the way I would go. I like this decision-making, this choosing, based as it is now on a lifetime of mountains big and small, home and away, reducing complexities to simplicities, at ease in the joy of going – and mindful of the Arab saying, ‘Hurry is the devil’. Not that hurrying was possible, that was denied by both the landscape and eighty-year-old joints. Our great Scottish explorer Joseph Thomson took as his motto an Italian aphorism, ‘He who goes carefully goes safely and he who goes safely goes far’.

The ground was sour and saturated (hence the wellies), smelling of vegetation’s decay, with orange-tinted grasses, mosses, heather, black peat, slimy pools. Every step needed care. Heather stems were lethally slippery. Progress however was helped by innumerable sheep trods which, from above, patterned the tweedy landscape in parallel lines. (There was an irony in the very beasts who caused this soggy desert providing the easiest way through it.) Here and there were green knolls and, invariably, they bore the rickles of grey stones pointing to the brave people of the past. The map noted the sites as airidh or shieling. But the people have gone, by demand or desire, and only the occasional ATV track indicates any working of the land today. How many generations of women and children had passed their summers up here, herding, making butter and cheese, the slopes echoing to songs and children’s voices? The ground would have been sweet-scented then.

I passed small parcels of sheep all day. (On the descent of the rockier heights I would laugh aloud on seeing an old ewe posing presumptuously on a boulder like a Landseer stag.) Walking had warmed me, not the sun, which lay behind horizon-anchored cumulus. Golden rays occasionally escaped to shoot up in to the sky, a sky the delicate blue of a blackbird egg. Down in a trough I was then ambushed by one of nature’s miracles, an experience overwhelmingly vital, yet of the almost impossible: silence, complete, total, unbroken silence, a sort of crystal clarity, enveloping all the senses, to leave the heart throbbing, standing transfixed in case the aura shattered, an experience quite wonderful and really ineffable. I have met the effect several times in the deserts south of the Atlas Mountains. With a group I once became aware of its presence and bade everyone stand still and be completely quiet, but someone moved a sandal, someone’s breathing could be heard, and there was no magic, no nothingness. They strained for what they never knew and which I couldn’t describe. You have to be alone and very still for this natural miracle. On Roineabhal when eventually I moved I became noise and broke the bubble of the experience. The passing of a silent raven overhead (Odin’s bird) wasn’t silence at all. I could hear the flurry of its wingbeats. Usually, however quiet, faint and far, wind makes noise, water makes noise, man makes noise – which is why one goes alone, to enjoy the talk-free companionship of the wild, to relish a respite from the inanities of life.

Height was gained slowly. The going became steeper and more heathery and the trods tended, as they do, to head along rather than up. The sun at last looked as if it was going to break out of prison so I scrambled up onto the spur, Cnoc Foinaval, a sort of base buttress of Roineabhal, and there met its flooding light. My pullover soon came off as I headed up, the ground now broken with slabs of rock, deeper heather and a skin of bog. I enjoyed picking a way through the mix, trying to keep my steps in that rhythm that appears from a distance just to glide. A short barrier of crag girdled the hill and gave a brief scramble then it was all much steeper and rockier. I kept my eyes on my feet, partly of necessity, and partly to hold back the big view for a summit surprise. Soon, just ahead, was some quite substantial walling and I wondered who could have built what, when, in such a spot. It proved a summit shelter, a horseshoe dyke with its back to the west. I’d arrived – and was duly astounded.

World on world seemed to open in the vast lightness of Hebridean distances. South, the big hills were alpine white in the brilliance, their names a rumble like distant thunder: An Cliseam, Uisgneabhal, Oireabhal, Tirga Mor, Huiseabhal – a mini Oberland – the night’s blizzard having singled them out in a linear painting that had left the rest of Harris and Lewis untouched. The far west group of Mealaisbhal, Tahabhal, Cracabhal, Griomabhal were faint, grey-blue against the western merging of sea and sky. South east rose the jumble of hills in the trackless heart of Pairc which those hungry for land had once hoped to tame (a stark monument to the land-raiders stands by the A859 just south of Baile Alein). But it was north and north east that truly astonished; between my stance and the road over to Calanais (Callanish) lay a crazy world woven on a warp of water and a weft of rock. A single loch, as complex in shape as a piece in a jigsaw, could reach into a dozen kilometre grid squares on the map, or a single grid square could hold a dozen lochs. Creator as Rothko. Far to the north in Lewis’s emptiest quarter were the projecting cones and whalebacks of Muirneag, Beinn Bhragair and Beinn Mholach, the last prefaced with a row of wind turbines, arms at rest. The naming of the hills was comforting for this sad, harsh world, shrouded into the mists of prehistory, fable and recent history, has known peoples much misused whose only desire was to be themselves.

The myriad waters all lay still. Only on the very summit was there a faint breeze, courteous enough to cool but not chill, Heart-happy, I sat to demolish pieces with egg and tomato and a scone with heather honey, fully conscious of the grace of such a day of glory given when we – so small – are possessed by landscape.

Christmas is often the worst time of the year but, over decades, a gang of us aimed to climb a hill every Christmas Day (and, a harder discipline, New Year’s Day) but this tradition had rather ‘weed awa’. Old men are only young for so long. (Ah, but I was young on Roineabhal!) I recalled some of those days back in the years when it knew how to snow: Beinn Eighe by the round of Coire Mhic Fearchair; Beinn a’ Ghlo’s trio of Munros when we watched an otter tobogganing in the snow on its tummy over and over for the fun of it; Fionn Bheinn, where we found a lost collie by the cairn; Beinn Liath Mhor, climbed from a high camp by Lochain Uaine; Conival and Ben More Assynt, gained from my first camper van; Fuar Tholl by a challenging ridge route; Slioch on another day of glory given. There were a few gaps: once recovering from taking part in a night rescue, or preparing for the first (of an unimaginable 53) visits to winter in the Atlas, or a family gathering after our father died, or sailing up Lake Malawi on the Ilala during a Cape to Kenya peak-bagging sabbatical.

The sun, past noon, was already lowering its head, the cold sharpening. Time to descend. To a new year of who knows what? ‘Everybody needs beauty as well as bread, places to play and pray in, where nature may heal and give strength to body and soul alike’. That’s John Muir. Robert Louis Stevenson, travelling with his donkey, wrote of the ‘Bastille of civilisation’. How lucky we are to have these safety valves, how easy to escape, to satisfy the insatiable itch of wanderlust, of wonder lust, be it an hour on Duncarrow, a day on Roineabhal, or months on great ranges.

Descending, I made something of a right-flanker to avoid the rock band and came down to a heathery shelf. Though concentrating fully my foot went through into a hidden hole and momentum felled me like a tree onto heather, luckily a surface soft as a duvet, but it reminded me of the uncontrolled chances of just being. Life is risky, if less so on the hills than on city streets. I circled round and down to more or less follow my upward route, at one stage being surprised by a boot-print in the mud, until I printed one the same beside it. I walked with a long shadow, trying to keep on the sunny side of any rise.

My mind ran on about the hill names I’d ticked off on the summit and those of Christmases past. What Gaelic I recognise is largely hill and map related though my first ever remembrance of speech is of a person who used to kiss me goodnight with a gentle, ‘Oidhche mhath’. Making the names of places in duplicate everywhere I find questionable. Baile Alein followed by Balalan is sensible, and helpful, for the anglicisation at least hints at pronunciation, but home in Lowland Burntisland, to see An t-Ailean Loisgte added is daft, this used neither in Fife nor in the Hebrides. Language is quite capable of sorting itself out, and does so, quite happily absorbing words from other languages or through inventive necessity. A word like pixels must have invaded nearly every language on earth. Reminds me of a programme years ago when a rather pompous Englishman was being very dismissive of Gaelic, pointing out its constant interjection of non-Gaelic words. ‘What, for instance,’ he blurted out, ‘is the Gaelic word for banana?’ The gentle Gaelic speaker’s reply was, ‘Just so, and what is the English word for banana?’

Two hours from the summit saw me back at the van. There were noisy geese once more, oysterpipers (as I thought them as a boy) flew over the road for Loch Eireasort, and a half-heard chorus came from a blowing cloud of distant gulls. And the same ancient dog walker I’d seen at the start passed, once again being towed by his shaggy mut. The plummeting temperature made the icing over of the puddles visible again, fronds and fingers suddenly appearing and spreading, quite freaky, but then wonders are found through eyes to the heart. The drive along the A859 was far more dangerous than my ascent of Roineabhal or Ivana and Enrique’s romp up the Clisham. The sun constantly blinded me with its dazzle through the windscreen. Winter sunlight however is often shortchanged; as soon as the Clisham and Todun were gained their bulk threw the world into curdling shadow. It was like having a curtain drawn down on the day. I sped the ups and downs and ins and outs back to the more temperate hideaway of Reinigeadal.

The hamlet has about ten scattered houses and above the road-end is the white-gleaming cottage which is the Gatliff Trust hostel. There are three Gatliff Trust hostels, the other two both being traditional old thatched-roof cottages, one on Berneray, one on South Uist (Howmore), all are renovated and comfortable and all have the pull of indefinable character. They were the inspiration of an eccentric Whitehall civil servant who saw the value of outdoor experience and threw himself into promoting bodies like the then new youth hostels’ movement. The Hebrides were special and had special treatment. The hostels are always open, inexpensive, and sit kindly within the community. Julius Kugy wrote that, ‘happiness should be the foundation stone of all mountaineering’ and Reinigeadal, Berneray and Howmore have given that glow to the happiness of many. Our Christmas day had registered high on the scale of fulfillment. We were all sad to leave.

My departing drive out was through snow showers and rainbows, escaping not a moment too soon. As the Hebrides left Tarbert the loch was arched over by a brilliant bow, but behind it, a wall to wall of dirty cloud was rushing in. Before we had passed Scalpay everything was blotted out in a major snowstorm. Reinigeadal would be isolated. The storm blew through and, looking back past our wake as we neared Uig on Skye, the whole Hebridean horizon was dazzling snow down to tide level. Once home in Fife I’d meet or hear from many friends who all enthused about that one magical, Christmas, day and praised God, gods or reality for a day of glory given.